Yesterday Olivier Rikken published this (1) compelling piece about disrupting insurance business models through P2P funding mediated by blockchain. I have been thinking about this area for some time. I agree with everything he said but would like to offer my take on how this could emerge, wider applications and why things should change.

I use as little insurance as I can get away with day to day as the terms and conditions I come across make me feel I’m being taken for a ride. The balance of power seems heavily in favour of the supply side of the business. Barak Obama illustrated this problem concisely in September 2009 when introducing his ambitions for a national health insurance scheme:

More and more Americans pay their premiums, only to discover that their insurance company has dropped their coverage when they get sick, or won’t pay the full cost of care. It happens every day.

One man from Illinois lost his coverage in the middle of chemotherapy because his insurer found that he hadn’t reported gallstones that he didn’t even know about. They delayed his treatment, and he died because of it. Another woman from Texas was about to get a double mastectomy when her insurance company canceled her policy because she forgot to declare a case of acne. By the time she had her insurance reinstated, her breast cancer had more than doubled in size. That is heart-breaking, it is wrong, and no one should be treated that way in the United States of America. (2)

Quite right too, but I extend his indictment to the wider insurance industry, not just healthcare and not just the USA. I consider this a problem of small print exploitation and see similar behaviour in many mass market industries. From mobile phone subscriptions (eg, unadvertised fair usage limits) through train tickets (eg, no guaranteed right to board without a seat reservation) to credit cards (think PPI). All of these industries and more could be reigned in by a public designing their own paperwork and showing the sellers what they want. What vendor doesn’t want their customers telling them, for free, exactly what they want? It certainly saves on the cost of market research.

Insurance policy documents are designed to make ultra clear what is and isn’t covered. To this end they contain long lists of conditions and situations and make for tedious reading. Perhaps my claim is unfair, it certainly is not scientifically researched: Policy writers have taken advantage of Joe Public’s reluctance to scrutinise legalise by introducing weasel clauses that invalidate claims with conditions and circumstances largely unrelated to the big print on the packet.

Travel Insurance is a common place product, sold by everyone from specialists to the post office. The products offer pay outs for broken bones, stolen cash, smashed gadgets and all the other dramas we fear. Time is a sensible pay out modifier. For instance if you break your leg 15 days after the start date of a 14 day contract you will receive zero. I don’t begrudge such a clause. However on a 12 month global backpacker package, what is the logic to it becoming invalid should the traveller return home at any point and then continue their trip? They are eligible in any country in the world during the insured time period, unless they have visited mum for a birthday weekend? That I imagine would surprise most buyers. It is also quite a likely event. The Guardian in 2015 reported:

Whether or not these are logical and fair exclusions developed by a mature and competitive insurance industry to give us reasonably priced coverage for the most common risks, they are tripping up the less well informed buying public. This is where I see blockchains and smart contracts shaking things up.

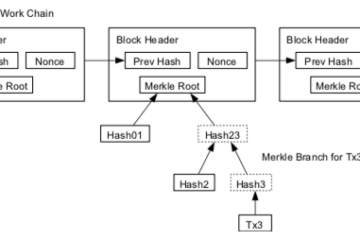

As Oliver implies, we can invite users and specialists to draft a plethora of insurance policies and contract templates related to various fields of risk (car, house, travel, heath, etc). Let’s open these to collaborative development under Commons licensing and open source development models. Now let’s write them as smart contracts that have precise and mechanical ‘deterministic’ behaviour. Buyers may now select a preferred contract from this public library and submit it for pricing to a range of insurance suppliers and sit back as the in-house models and risk machines pump out quotes, all based on exactly the same policy. This is a key change to current practice where cross comparison is impractical and range is limited. A consensus will build behind the contracts that suit most people and it will become trivial for a user to pick the most popular travel insurance template, price it up, take the cheapest and never bother reading the small print if they don’t want to. The difference now is that they are putting their faith in contracts designed by parties uninterested in the financial outcome of the contract and also ‘voted for’ by the popular demand of buyers. What’s more, the smart contract will play out the same, no matter who takes the other side of the deal. The buyers now represent a united force more equal in power to the sellers. Business opportunities are created for specialist contract writers to offer customisation of these contracts for niche requirements or even build something entirely from scratch for the more adventurous buyer. The price of this work will be distinct from the price of the insurance.

Oliver talks about the cost cutting ability of a smart contract blockchain through the automatic processing of payments. I believe costs can be driven down even further by setting up algorithmic insurance intermediaries that require no profit margin at all. Consider the existing insurance firms as middle men whose role is to best manage the incoming premiums against the outgoing compensation distributions. They are incentivised by profit which means maintaining as much of the incoming premium by paying out as little compensation as possible. A cheaper model results when that role is given to a manager whose aim is to balance incoming and outgoing as closely as possible with zero profit. In the era of big data, designing such an algorithm to conserve a sufficiently large buffer pool such that it can remain solvent and competitive doesn’t seem outlandish. Again there is room for enterprise here by firms who want to offer better algorithms that are able to price cheaply while having very long track records of solvency. These funds will need seed funding and bootstrapping an insurance firm is costly so there are business opportunities here. That does reintroduce profit margins but the economic pressure of the automatic, decentralised non-profit core will keep such profits and most importantly, the balance of power, in check.

While blockchains have lots of practical benefits in certain areas one of their most exciting applications is in creating balanced market places where monopolies and cartels do not outweigh a united and empowered public.

Sources:

(1) http://www.coindesk.com/blockchain-p2p-insurance-models/

(2) https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-a-joint-session-congress-health-care

(3) http://www.theguardian.com/money/2015/jul/05/travel-insurance-pay-out-disaster-small-print